Electric Language

Ulrike Domahs from unibz’s Faculty of Education is poised to open a new lab for Cognitive Educational Science that will allow EEG researchers to delve further into the mysterious enigma that is the human brain.

People think we can read their minds with it, but we can’t!” Ulrike Domahs is talking about the EEG machine—those not-so-stylish skullcaps that measure the brain’s electrical activity through electrodes placed on the scalp. But unlike a creepy scene from a sci-fi movie, Domahs’ use of the machine is giving us elegant (and totally un-scary) insight into how the human brain processes language. Domahs is a German-language professor from the unibz Faculty of Education and is the Director of the new Cognitive Educational Science (CES) Laboratory in Brixen/Bressanone. The lab is open to all researchers interested in studying the cognitive processes involved in the 20 million billion electrical commands that our brain’s neurons are sending out every second.

Personally, I prefer them on my feet

An electroencephalograph (or EEG) represents this neural chatter as waves. The technology is not new by any means. Back in 1929, a “brooding and introverted” German scientist, Hans Berger, watched as his rudimentary EEG scratched out the first inky-black brain wave of a 17-year-old college student by the name of Zedel. Within a few decades the EEG had become the staple tool of cognitive science. Scientists eventually identified six speeds of brainwaves—infra-low, delta, theta, alpha, beta and gamma—an orchestra of low to high bandwidths whose interactions are fundamental to understanding neurological disorders, sleep patterns and language. Ulrike Domahs’ research is based on an application of EEG technology called Event-Related Potentials (ERP). This approach measures the time it takes for the brain to react to a stimulus or event and the extent of that reaction. For example, if a friend tells you: “My wife spread butter and socks on her toast this morning”, your brain will register a negative shift on the EEG recording at about 400 milliseconds after hearing “socks” (the so-called N-400 effect). By comparing the N-400s of many individuals, Domahs can see patterns in how the brain processes language under different conditions.

Our Brainy Tongues

“We used to think about language processing from the monolingual adult’s perspective. Therefore, it was conceived of being quite uniform across people”, says Domahs of her work. “But we now know that it is affected by the amount of experience you have with a language. Therefore, it is important to know what’s going on in the brains of those learning a language, as well as those who are learning more than one language.” To get an overview of this area of language processing, Domahs has performed ERP studies with many different tongues— Turkish, Arabic, Italian, English, German, to name a few—as well as many different age groups. In particular, she has worked with children to observe the development of their mental lexicons, the brain’s piggybank of information about a word’s meaning, pronunciation, and other qualities. She also looked at how children use language rhythm to process words with different grammatical endings. (An example is the singular and plural forms of the German for dogs, cats and birds: Hund vs Hund(e), Katze vs Katze(n) or Vogel vs V(ö) gel.) In addition, she has worked with children with language impairment as well as with adults with a history of developmental language impairment to find out how language processing is affected by language disorders. Domahs will soon be comparing how Italian-German bilinguals and German monolinguals process language rhythm to see if the processing of rhythm changes when Italian and German speech rhythms coexist. Research such as this is important in South Tyrol, where questions of second-language acquisition are ever-present. We still don’t know enough about the difference between mono- and bilingual language processing, but whatever language or languages there are in our noggins, Domahs’ research may shape the way we teach them them in the future.

In all these years of research has Ulrike Domahs ever slipped the skullcap on her own head to take a look at her brain waves? “Of course,” she says. “It was one of the first things I did when I decided to go on this adventure. It is very important to know how it feels for the participants. It doesn’t hurt at all. It’s like being in the chair of a hair salon.”

Related Articles

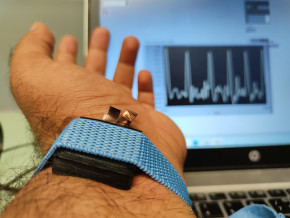

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.