On Kenyan Soil

Felix Greifeneder took a trek across Kenya last April for a EURAC-led project on soil moisture mapping. Night driving without headlights, eating a meal of goat and ugali polenta in

the Great Rift Valley—it wasn’t an average research week for Felix. Here’s his travelogue:

Day One – Thursday April 13, 2016:

First Impressions As my colleague Marc Zebisch and I take the last step from the plane onto the tarmac at Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, the first thing that strikes me is the temperature. I had been expecting a blast of tropical humid air in my face, but instead, the midnight breeze that greets us is remarkably cool and dry. Rainy season is late this year. The country of 36.6 million people has been struggling with a decades-long drought, and food shortages have worsened since 2012. Our remote sensing research is designed to help agriculture in the country. Funded by the European Space Agency’s TIGER initiative, which promotes the use of Earth Observation (EO) data to properly manage water resources in Africa, our hope over the next week is to begin work extending EURAC’s soil moisture mapping technology to a Kenyan environment.

Day Three – Friday April 15, 2016:

Exchange of Competences Marc and I give a workshop on remote sensing and soil moisture to our Kenyan partners at RCMRD (Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development) and LocateIT (a leading ICT company in location-based products and services), as well as a list of invited academics and public officials—about 30 to 40 participants in all. Remote-sensing technology is particularly useful in African countries, as there is no network of meteorological monitoring stations to monitor the soil in situ. I’m pretty blown away by the response at the workshop: I’m used to an average level of feedback at these presentations, but the Kenyan group today is very enthusiastic about the potential of what we are proposing to do in their country. There’s even a pair of scientists from an institute for infectious disease research at the workshop: since insect populations are linked with soil moisture, they are particularly interested in our research; it’s an application that I had not even considered in my research.

Day Four – Saturday April 16, 2016:

The Journey to Eldoret Today is the start of the journey to which I’ve been looking forward. Together with Degelo Sendabo, the Head of Remote Sensing at RCMRD, and Erick Khamala from LocateIT, Marc and I hop in a chauffeured passenger van to go to our test sites in the regions of Uasin Gishu and Elgeyo Marakwet, northwest of Nairobi. It’s a six-hour, 314-km trek from Nairobi to Eldoret, passing through the Eastern Rift Valley. As we descend the 700m wall of the 6,000km tectonic fault that runs north-south in eastern Africa, I am struck by the complete change in the landscape as the valley’s microclimate takes over. The scenery above looked to me not much different from that of Central Europe (there were even pine-tree forests). But in the valley the vegetation has turned into what you might consider classic sub-Saharan savannah. It’s very hot. No agriculture here—just goat and sheep herding (mixed with the occasional zebra or monkey). Driving along the floor of the valley, we stop for lunch at a little green shack of a restaurant. Here we get our first real introduction to Kenyan cuisine: Marc and I have to choose our own cut of meat from a dead goat strung up in the kitchen. After waiting for what seems like an eternity (each meal in Kenya usually lasted two hours to cook and eat), we eat the unsalted goat with our fingers, along with a ball of ugali, a polenta-style dish made of maize flour and boiled to form a dough.

Day Five – Sunday April 17, 2016:

Fieldwork Reconnaissance On Monday there is to be a flight overpass of the ESA’s Sentinel 1 satellite. As we are planning to take ground measurements at the same time to validate the satellite’s data, today we are driving through our test sites to scout out our measurement locations. The farmers’ fields are very empty. Because of the late start to the rainy season, I am told that many of them haven’t even started to seed their crops yet. At each location, Erick does a great diplomatic job of getting permission from the farmers (he is the only one who speaks Bantu Swahili). Our presence here does not go unnoticed. The sight of two white guys walking around with scientific instruments tends to turn heads in Kenya; wherever we stop, Marc and I are soon surrounded by a throng of friendly bystanders wanting to know what we’re doing and why, most of them young children. Erick tells us that 42 percent of the Kenyan population is under 16, and the population grows at 2.7% annually. This, too, must put stress on dwindling water supplies, I think.

Day Seven – Tuesday April 19, 2016:

The Return to Nairobi The satellite overpass ground readings were successful yesterday. Erick and Degelo have learned the measuring techniques perfectly. Now we are set to return to Nairobi and then on towards home. It will not be so easy, though, to get out of Kenya. Our driver tries to start the van at 8am, only to find that the electrics have failed. So—change of plans—we are treated to a day-in-thelife of an Eldoret automobile garage, which is no more than an empty lot between two buildings in a city block. As we wait out the interminable time it takes to determine the problem, order a part, try to fix it, find there’s another problem, order a part, and so on, we get to experience the mayhem of Eldoret, a town of about 300,000 that straddles the truck-lined Kenyan-Ugandan highway. The problem finally resolved about midday, we make our way home. Twenty clicks outside of Nairobi, as the sun dips below the horizon, our driver turns on the headlights. It becomes apparent that the electrical problem hadn’t been fixed at all— and we have very little battery left. I have real respect for this driver now because I wouldn’t have continued: after rolling with the parking lights only, the last couple of kilometers are a hair-raising experience of slow driving on the pitch-black section of highway complete with cars racing up behind us. I suppose on a successful research trip like this, at least one life-threatening adventure is all right.

Related Articles

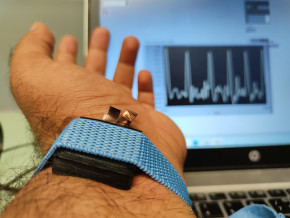

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.