Language Learning: incentives are essential!

Jemma Prior is a well-known face among language learners at unibz. She started working at unibz two decades ago. For the first three years, she was teaching at the Language Centre but, from 2001, she has been teaching specialized English language at the Faculties; first at the Faculty of Economics, then also for Computer Science, Design and Art, and Science and Technology. The years spent giving classes to university students have taught her many things, but an important one is: a good teacher must be able to involve his or her students and to adapt the study program to meet their needs. This quest for the perfect syllabus also guides Prior’s research activity which revolves around how to implement a special study program that is, at the same time, relevant and appealing.

In a scientific paper you published recently - Integrating extra credit exercises into a university English-language course: how action research provided a framework to identify a practical problem – you focused on a very specific problem: how the teacher can increase the attendance of economics students who are skipping classes. So how did you succeed in tempting the students back to the English classes?

First of all, as I explain in my article, I gathered data on the English language problems of the students. I sent them questionnaires over a three-year period and I interviewed all the academic staff that were teaching in English at the Faculty of Economics at the time in order to find out what difficulties the students encountered during their lessons. Generally, I was interested in discovering what kind of problems learners have when studying in English at the Faculty.

What problems did you identify?

They were mainly of two kinds. On the one hand, we have students who don’t feel very confident with their speaking skills. Many colleagues agreed on this and said that many students are afraid to speak. For the academic staff, it’s therefore difficult to tell if the students don’t know the subject or if they have problems with English. The students pointed out their writing skills are also weak, another issue which all the professors were aware of.

How did you use the gathered data?

These data revealed where I should focus my efforts. I’ve designed an approach to teaching that optimizes the relatively little amount of time available for the course in order to provide as much speaking and writing practice as possible.

Which strategies did you apply to encourage them to come to class?

Basically, I used what economists call “incentives”. In my case, these were “extra credit exercises” where they could get bonus points to add to their final grade if they were in class and completed a test-like exercise. The idea behind it was that if they were in class to do the extra credit exercise, they would also be practicing their speaking and writing skills. They have to be in class and thus they use the language.

If you give students - especially at university - the ability to take decisions about how they’re learning, this will be more effective

Did this measure prove effective?

Absolutely. It turned out that they attended more and more regularly. The biggest difference I’ve noticed so far is that the weaker students do better. The actual grade average hasn’t changed that much but the number of people now passing the exam – who before scored 16 or 17 – has increased.

An important part of your approach is the involvement of your students in the preparation of portfolio, isn’t it?

Yes. That is a part of the syllabus that they can negotiate with me. I call this a “blended approach”: part of the syllabus is compulsory and decided by the teacher but a portion of it can be modelled according to the students’ interests. Then, together as a group, we negotiate what language practice they do, how many questions they do, what topics they normally investigate. For instance, we have adopted the book Freakonomics. They can pick out a section or sections and then write an analysis or a summary of it. In the portfolio there’s also a presentation they have to prepare for the oral exam – again topics that are chosen together with the students, so this part of the course basically changes every year.

Your research concentrates on two different approaches you use in class. What are they?

One type focuses on speaking practice and is known as a “product approach” to syllabus design, where you look at the end-product, that is the goal you want to achieve. I’m mixing it with a “process approach” that is based on this idea of involving the students in the decision-making process. The idea is also that when I negotiate with them, they use their language skills. That’s the blend, it’s working together.

And the type of writing they choose in the portfolio is the one they think is most useful for them, is that right?

Yes, the focus here is on the learner’s autonomy. If you give students - especially at university - the ability to take decisions about how they’re learning, this will be more effective because they feel more responsible and motivated in the process. Normally, when you read classroom-based research, teachers usually use either one or the other approach to syllabus design, and most of the times the “product” approach is used. What I’ve done is basically taken the best parts of the two approaches and blended them in my teaching activity.

Related Articles

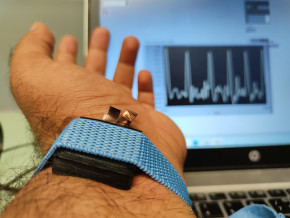

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.