Cyprus Stalemate

What began in 2014 as “an exceptional opportunity” for peace on the island of Cyprus ended this July with angry fingers pointing across a dinner table at the final, ill-fated meeting in Crans-Montana, Switzerland. Eurac Research’s own Joseph Marko—an expert in minority rights, ethnic conflict and nationalism—was drafted to the UN Cyprus Talks in June 2016 as the UN’s legal advisor on human rights. He gives us his perspective from the front lines of the 54-year ethnic conflict.

What was your role around the negotiation table?

Joseph Marko: The Cyprus reunification process wants to establish a bi-communal and bi-zonal federation, following a principle of political equality between Turkish and Greek Cypriots. However, the legal institutional framework they foresee is a very complicated one. How do you avoid discrimination on ethnic grounds when you want to construct a federal state on the basis of ethnicity and power-sharing between these two ethnic groups? How do you find the correct balance between the autonomy of the two constituent states and their integration? How do you balance individual and cultural rights within the institutional group mechanisms? These are tricky issues. I was hired given my experience working as a judge in the Bosnian Constitutional Court, as well as in South Tyrol.

Another issue is how you negotiate a federal system when one of the two parties is not recognised internationally. How does the specific minority situation of the Turkish Cypriots affect the deliberations?

Marko: It is an asymmetric negotiation process from the outset, with the Greek Cypriot government insisting that they are the only legally, internationally-recognized part of the island, and what is placed in the north is an illegal occupying regime with no legitimacy in international law. Turkish Cypriots do not see themselves as a minority but as a co-nation. They argue that Cyprus is also their homeland and they cannot be reduced to a minority position. Turkish Cypriots say they were kicked out of institutions in 1963 and that their existence was threatened in 1974, when the military junta in Greece toppled the government in Cyprus and tried to assassinate the president of Cyprus. These are historic wrongs which have left them afraid. For their part, the Greek Cypriots argue that their cultural heritage will be threatened if more Turks are settled in Cyprus—since 1974, three generation of Turks from Anatolia have been brought to Cyprus as a way to change the demographic balance on the island.

The Turkish occupation of the north has been one of the major stumbling blocks at the negotiations. It stems from the rights of the three “guarantor countries”—Turkey, Greece and Britain—to militarily intervene when one Cypriot group threatens the other. Is there any credence to the Turkish minority’s claim that they require a military guarantor in 2017?

Article 4 of the Treaty of Guarantee was the legal background for the Turkish military invasion in 1974, but there is no legal basis to keep 40,000 Turkish troops in Cyprus today. The Greek Cypriots argue that if Cyprus is to become a normal European country as member of the European Union, there can be no troops or military intervention rights. But there was a second major issue at the table—governance. For the Turkish Cypriots, a unified federal Cyprus would require a rotating Greek and Turkish presidency, as well as a 50 per cent share of civil servants in the federal executive and judiciary. The Greek Cypriots are hesitant to recognize this claim. They argue that if Turkish Cypriots make up only 25 per cent of the entire population, why should they be given 50 per cent of the power? In the background is the ascribed minority problem again. The Turkish Cypriots answer: “If you don’t recognize the rotating presidency you again treat us as a minority, not as a co-nation with political equality.” The Greek Cypriots were not willing to give that away at the beginning of the conference, but by the end they said if Turkey was to give up all troops and intervention rights, they in turn might give Turkish Cypriots a rotating presidency. This is the reason why the conference failed: both sides insisted that the other side had to make the offer first. That’s what didn’t happen.

You mean that’s what didn’t happen at the final dinner on July 5th, held in the presence of Secretary-General António Guterres, when the negotiations were said to have gone off the rails? Were you at that dinner?

Marko: I was not at the dinner table that night. In order to reach a break-through in the negotiations, the “working dinner” took place at the highest diplomatic and political level with only the SG and his two special advisers, the foreign ministers of the three guarantor powers, the High Representative of the EU for foreign affairs and security policy, and the two leaders of the two communities. But all the teams of the parties, including the UN, were sitting in one of the adjacent rooms, waiting to be called in to give legal expertise. At four o´clock in the morning, the SG informed the UN team, including me, personally that all the efforts to reach a compromise had failed.

How could the talks break down so rapidly that night?

Marko: It’s a question of trust building. There was trust built two years ago when the two leaders of the island, Nicos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akıncı, signed a joint declaration to establish a bi-communal and bi-zonal federation on the basis of political equality. They began to work hard on the translation of these vague principles into a legal framework. Unfortunately, the atmosphere in the working groups collaborating on these different issues deteriorated more and more as the competing and opposing claims were laid out in detail on the table. Then there was a decisive break in the trust at the end of last year, when the Turkish government began to wonder if this was a serious negotiation process or only for the Greek Cypriot leader’s political purposes at home: in February 2018, there will be presidential elections in the internationally recognised part of Cyprus and President Anastasiades will run again as a candidate in the elections. The Turkish side began to argue that he’s not interested in a compromise, but in winning votes, and in the end, this completely destroyed the trust on both sides.

Related Articles

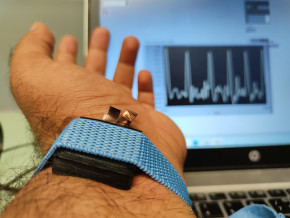

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.